The allure of mechanical watchmaking has captivated enthusiasts for centuries, yet the path from admiring a timepiece through glass to understanding its inner workings remains shrouded in mystery. Most descriptions of watchmaking education focus on curriculum details—components, tools, historical context—but they rarely address the visceral transformation students experience when they first hold a movement in their hands.

This gap between expectation and reality creates both fascination and apprehension. Those drawn to a watchmaking class often wonder whether the intricate craft is truly accessible or remains the exclusive domain of career professionals. The answer lies not in theoretical knowledge but in the progressive recalibration of perception that occurs when you engage directly with mechanical systems designed to measure time itself.

The journey from passive observer to active practitioner involves more than manual dexterity. It requires developing new forms of vision, embracing productive failure, and ultimately internalizing the logic that transforms springs and gears into precise temporal instruments. Understanding this transformation reveals what truly happens inside the workshop—and why the experience fundamentally reshapes how you perceive every watch you encounter afterward.

The Watchmaking Transformation in Brief

Watchmaking classes offer an experiential journey beyond technical instruction. Students progress through distinct phases: initial mechanical contact that reveals the paradox of fragility and resilience, diagnostic skill development that transforms observation into analytical vision, controlled failure scenarios that reframe mistakes as learning tools, and the cultivation of temporal intuition that connects mechanical understanding to embodied knowledge. The transformation extends beyond the classroom through sustained practice strategies and community engagement that preserve skills without professional workshop access.

The First Dismantling: What Actually Happens When You Touch a Movement

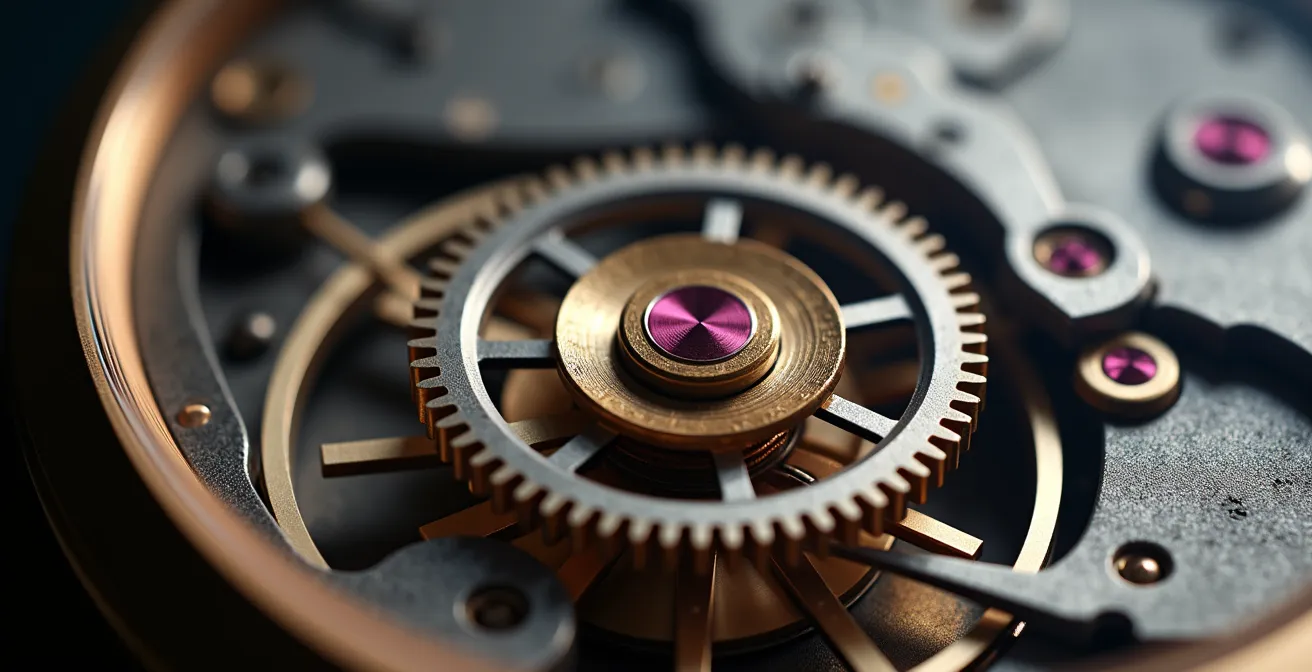

The moment a student first handles a mechanical movement creates a cognitive dissonance that textbooks cannot prepare you for. The components appear impossibly delicate—hairsprings thinner than human hair, jewels the size of pinheads, screws requiring specialized tools to grip. Yet instructors quickly demonstrate that these mechanisms possess surprising resilience when handled with proper technique.

This paradox forms the foundation of hands-on learning methodology. Professional watchmaking courses typically maintain class sizes of 5 students maximum according to AWCI’s 2024 remote learning standards, ensuring individualized attention during these critical first interactions. The intimate setting allows instructors to correct technique immediately, preventing the formation of habits that could damage movements or impede skill development.

The pedagogical sequence follows a carefully structured progression. Students begin with observation exercises—examining movements under magnification, identifying components without touching, understanding spatial relationships through visual analysis alone. This preparatory phase builds mental models before physical engagement introduces the complexity of three-dimensional manipulation.

Training movements serve as the initial practice medium—often vintage ETA calibers selected for their educational value and component accessibility. The ETA 6497, with its larger components and straightforward architecture, provides the ideal starting point for developing fundamental manipulation skills without overwhelming complexity.

The recalibration from isolated component thinking to systems comprehension represents the first major cognitive shift. Students initially perceive the movement as a collection of separate parts, but repeated assembly and disassembly reveals the integrated nature of gear trains, escapements, and regulation systems. This understanding emerges through tactile feedback—the resistance of properly seated jewels, the smooth engagement of correctly aligned gears, the subtle spring of the click mechanism.

What I didn’t know was how approachable the whole process was going to be. The instructors were humble sages. They had honed our tools and organized a meticulous and fluid learning environment.

– Student testimonial, Hodinkee

Early errors provide essential feedback about mechanical tolerances and system dependencies. A balance wheel that refuses to oscillate reveals misalignment in the pallet fork. Excessive endshake indicates incorrect jewel seating. These diagnostic moments transform mistakes from sources of frustration into information-rich learning opportunities that build troubleshooting intuition from the very beginning of training.

Developing Diagnostic Vision: Reading a Movement Like a Watchmaker

Professional watchmakers possess a form of perception that transcends simple component recognition. This diagnostic vision allows them to detect microscopic wear patterns, identify contamination invisible to untrained eyes, and interpret subtle acoustic signatures that reveal escapement dysfunction. Developing this perceptual acuity represents one of the most valuable yet least discussed outcomes of formal watchmaking education.

The training begins with systematic observation protocols. Students learn to examine movements under varying magnification levels, identifying normal versus abnormal characteristics. Pivot wear appears as darkened areas on bearing surfaces. Oil degradation manifests as discoloration or migration patterns. Dust contamination reveals itself through irregular distribution on component surfaces.

Acoustic analysis forms a parallel diagnostic stream. The healthy tick of a well-adjusted escapement possesses distinct rhythmic qualities—consistent interval timing, balanced amplitude in both directions, absence of rattling or scraping sounds. Students develop this auditory discrimination through repeated exposure, learning to isolate specific acoustic signatures from the complex soundscape of a running movement.

The watches are capable of measuring movement subtleties or hand-tremor amplitudes and frequencies with much greater precision than clinical documentation or even human vision

– Varghese et al., Sensor Validation and Diagnostic Potential of Smartwatches in Movement Disorders

The progression from symptom observation to causal diagnosis requires understanding mechanical relationships within the movement. A watch that stops after partial winding might indicate mainspring barrel friction, broken gear teeth, or escapement interference. The diagnostic process involves methodical elimination—testing each subsystem to isolate the failure point.

Basic movement diagnostic steps

- Push in the crown and check for hacking second function

- Turn the crown clockwise to wind up the movement

- Listen for consistent tick-tock rhythm indicating proper escapement function

- Check for amplitude consistency through visual observation of balance wheel swing

Three-dimensional spatial reasoning develops through hands-on manipulation. Students learn to visualize how components interact across multiple planes—how the cannon pinion drives the minute wheel, how the intermediate wheel transfers power to the escape wheel, how the pallet fork interacts with the balance roller jewel. This mental modeling allows anticipation of how adjustments in one area will affect performance elsewhere in the system.

| Diagnostic Method | Accuracy Rate | Detection Range |

|---|---|---|

| Visual Inspection | 75-80% | Major defects only |

| Acoustic Analysis | 85-90% | Escapement issues |

| Timing Machine | 95-99% | Rate variations ±0.1s/day |

Implementation of Diagnostic Training in Professional Watchmaking Programs

The Nicolas G. Hayek Watchmaking School curriculum emphasizes diagnostic skills through their WOSTEP program, where students spend 3000 hours developing the ability to identify and troubleshoot movement complications. Graduates report 90% success rates in diagnosing complex watch issues within their first year of professional practice.

Pattern recognition accelerates through exposure to multiple movement types. While initial training focuses on standard three-hand calibers, progression to complications—chronographs, annual calendars, moon phases—expands the diagnostic vocabulary. Each new mechanism introduces unique failure modes and adjustment requirements that deepen overall mechanical comprehension.

The Deliberate Mistakes: Learning Through Controlled Failure

The anxiety of causing irreversible damage haunts many students during early training sessions. This fear often proves more paralyzing than actual technical difficulty. Progressive watchmaking pedagogy addresses this psychological barrier through structured failure exercises—intentionally creating problems that students must then diagnose and correct.

Instructors might over-lubricate a jewel bearing, demonstrating how excess oil migrates and attracts contamination. They might reverse assembly sequence, showing how improper order prevents correct component seating. These controlled scenarios reveal the boundaries of mechanical tolerance while proving that most errors are correctable rather than catastrophic.

The transformation from error-avoidance to error-analysis represents a crucial mindset shift. Students begin viewing mistakes as diagnostic information rather than personal failures. A broken staff during disassembly reveals excessive force application. A scratched bridge indicates improper tool selection. Each error provides feedback about technique that accelerates skill refinement.

Professional certification programs incorporate substantial practice hours specifically for this iterative learning. Industry standards typically require 5,120 hours for a two-year watchmaking school program, with significant portions dedicated to repetitive assembly and disassembly that normalizes both success and failure as parts of the learning process.

The instructor-to-student ratio enables real-time intervention during critical moments. When a student applies excessive torque to a case back, the instructor can correct technique before thread damage occurs. When pivot alignment proves challenging, hands-on guidance provides kinesthetic learning that verbal instruction cannot replicate. This immediate feedback loop compresses the time required to develop reliable technique.

He said; ‘It depends on how long you live and how much of that time is spent on the learning’. Remembering what my master/mentor told me at the beginning when I asked, ‘How long will it take for me to become a real watchmaker?’

– Professional watchmaker reflection, NAWCC Forum

Deliberate over-challenge exercises push students beyond current competency in supervised environments. Attempting a complicated repair beyond current skill level—under instructor supervision with practice movements—reveals knowledge gaps while demonstrating achievable next steps. This scaffolded approach to difficulty prevents stagnation while maintaining psychological safety.

The emotional journey from trepidation to confidence emerges through accumulated small successes. Each correctly assembled movement, each successfully diagnosed fault, each recovered error builds the self-efficacy necessary for independent practice. The instructor’s role evolves from demonstrator to consultant as students internalize both technical skills and problem-solving frameworks.

From Mechanical Logic to Temporal Intuition

The deepest transformation in watchmaking education occurs when mechanical understanding evolves into temporal intuition. Students progress beyond knowing that an escapement regulates energy release to viscerally comprehending how oscillating systems convert stored potential energy into measured intervals. This shift from intellectual knowledge to embodied understanding represents the philosophical core of horological craft.

Physical manipulation reveals relationships that theoretical study obscures. Feeling the resistance of the mainspring as it winds communicates energy storage in ways diagrams cannot. Observing the balance wheel’s oscillation—its acceleration from rest, peak velocity at center, deceleration to momentary stillness—demonstrates isochronism as lived experience rather than abstract concept.

The escapement’s function becomes intuitive through repeated observation of its mechanical dance. The escape wheel tooth contacts the pallet stone, transferring impulse to the pallet fork, which pivots to release one tooth while locking the next, simultaneously delivering energy to the balance roller jewel. This choreographed sequence, repeated 28,800 times per hour in standard movements, transforms from bewildering complexity to elegant simplicity through familiarity.

| Training Phase | Key Understanding | Skills Developed |

|---|---|---|

| Initial Assembly | Component identification | Manual dexterity |

| Intermediate Practice | System interactions | Diagnostic thinking |

| Advanced Integration | Energy flow comprehension | Intuitive problem-solving |

Students experience breakthrough moments when mechanical relationships crystallize into coherent understanding. The realization that the entire gear train exists solely to reduce mainspring power to useful levels for the escapement. The recognition that regulation involves not changing the escapement itself but adjusting the active length of the hairspring to alter oscillation frequency. These insights reorganize existing knowledge into functional frameworks.

The relationship with personal timepieces transforms permanently after hands-on training. Watches transition from aesthetic objects or status symbols to comprehensible machines whose every function reflects deliberate engineering decisions. Appreciating luxury watch selection evolves to include technical consideration alongside design preferences.

Transformation of Perception in Watchmaking Students

Christian’s online watchmaking course demonstrates how students progress from mechanical assembly to intuitive understanding. After completing the 5-hour foundational course, students report a fundamental shift in how they perceive timepieces—moving from seeing collections of parts to understanding integrated systems where energy flows through precisely calculated pathways.

Market dynamics reflect the precision difference between mechanical and quartz technology, with 71% market share for quartz due to superior accuracy of ±15 seconds per month versus mechanical ±5 seconds per day. Yet watchmaking students develop appreciation for why mechanical movements command premium prices despite inferior timekeeping—the craftsmanship, complexity, and historical continuity they represent.

This evolved perspective extends beyond horology. The systems thinking developed through movement analysis applies to understanding any complex mechanism. The diagnostic methodology transfers to troubleshooting in unrelated domains. The patience cultivated through repetitive practice proves valuable across creative and technical pursuits. The transformation is cognitive and perceptual rather than merely technical.

Key Takeaways

- Watchmaking training transforms perception through hands-on contact with mechanical systems and diagnostic skill development

- Structured failure exercises reframe mistakes as essential learning tools rather than catastrophic errors

- Students develop temporal intuition by physically manipulating components that regulate and measure time

- Professional courses maintain small class sizes enabling real-time technique correction and individualized instruction

- Skills remain valuable beyond horology through transferable systems thinking and diagnostic problem-solving frameworks

After the Class: Sustaining Skills Without Daily Practice

The conclusion of intensive watchmaking training creates a practical dilemma for non-professional students. Without daily access to workshop facilities, movements, and specialized tools, hard-won skills risk degradation. Addressing this challenge requires strategic approaches to skill maintenance and continued learning that fit within amateur constraints.

Home practice remains viable with modest investment in essential tools and practice movements. Vintage mechanical watches from online auction sites provide affordable training material—damaged pieces that would otherwise be discarded serve perfectly for disassembly practice. A basic workbench setup requires minimal space while maintaining the organized workflow developed during formal training.

Maintaining watchmaking skills post-training

- Practice on affordable vintage movements from online suppliers

- Join local horological society chapters for monthly meetups

- Subscribe to professional publications for technical updates

- Attend annual watchmaking conventions for continuing education

- Maintain a home workbench with essential tools for regular practice

Community engagement provides both motivation and knowledge exchange. Horological societies exist in most major cities, offering regular meetings where members discuss technical challenges, share tools, and collaborate on restoration projects. These networks prevent the isolation that often leads to skill atrophy while providing access to expertise beyond individual training.

The professional watchmaking field offers viable career paths for those discovering passion during initial training. Average compensation data shows watchmaker salaries at $45,290 per year according to 2024 Bureau of Labor Statistics data, with significant variation based on specialization, location, and employer type. Independent watchmakers serving collectors often earn substantially more through boutique services.

Skill retention correlates directly with practice frequency. Research on technical skill maintenance demonstrates predictable degradation patterns without regular application. Students who dedicate even minimal weekly practice—one to two hours disassembling and reassembling movements—retain substantially more capability than those who abandon hands-on work entirely after course completion.

| Time After Course | With Practice | Without Practice |

|---|---|---|

| 3 months | 95% retention | 70% retention |

| 6 months | 90% retention | 50% retention |

| 1 year | 85% retention | 30% retention |

Advanced training opportunities allow progressive skill development beyond foundational courses. Specialized workshops focusing on complications, restoration techniques, or specific movement families provide structured learning paths for serious enthusiasts. These intensive sessions, often weekend or week-long formats, accommodate working professionals while building expertise incrementally.

The transformation from watch collector to practitioner-collector fundamentally alters acquisition decisions. Understanding complications from assembly experience reveals quality differences invisible to untrained observation. Recognizing finishing techniques—Côtes de Genève, perlage, anglage—from hands-on practice enables informed appreciation when evaluating pieces. This knowledge enriches collecting through technical dimension that complements aesthetic judgment, particularly when buying luxury watches from various sources.

The transferable cognitive skills developed through watchmaking training extend value beyond horology itself. Systems thinking applies to understanding any complex mechanism. Diagnostic methodology transfers to troubleshooting in unrelated technical domains. Patience and precision prove valuable across creative pursuits. These broader competencies justify the time investment regardless of whether watchmaking becomes profession, serious hobby, or enriching temporary engagement.

Frequently Asked Questions on Watchmaking Classes

What movement do beginners start with in watchmaking classes?

Most watchmaking courses begin with the ETA 6497 movement, which features 60-65 components in a larger format that facilitates learning. This hand-wound caliber provides straightforward architecture without overwhelming complexity, allowing students to develop fundamental manipulation skills before progressing to more intricate automatic or chronograph movements.

How long does it take to complete a professional watchmaking course?

Professional certification programs typically require two years of full-time study, totaling approximately 5,120 hours of instruction and practice. Intensive recreational courses range from single-day introductory sessions to week-long comprehensive programs. Advanced specialization in complications or restoration may require additional training beyond foundational coursework.

Do I need prior experience to join a watchmaking class?

No prior watchmaking experience is necessary for beginner courses. Most programs assume students arrive with enthusiasm rather than technical background. Basic manual dexterity and patience prove more important than existing mechanical knowledge, as instructors build skills progressively from fundamental concepts through increasingly complex procedures.

What tools do I need to practice watchmaking at home after completing a course?

Essential home practice requires a basic toolkit including screwdrivers, tweezers, hand removers, a movement holder, and magnification (loupe or microscope). Practice movements can be sourced affordably from vintage watch suppliers. A clean, well-lit workspace with proper storage for components completes the minimal setup necessary for skill maintenance between formal training sessions.